In 1844 a group of friends met at Glen Cottage in Torquay’s Park Street. At that gathering, it was agreed to set up an institution to promote the study of the natural sciences.

This became the Torquay Natural History Society which went on to initiate Torquay Museum. In 1874, after relocating several times as its collections grew, the Museum found a forever home in its grade II Venetian Gothic base in Babbacombe Road.

In 1874, after relocating several times as its collections grew, Torquay Museum found a forever home in Babbacombe Road

In 1874, after relocating several times as its collections grew, Torquay Museum found a forever home in Babbacombe Road

That such a learned society should begin in a town with a resident population of only around 6,000 may seem somewhat peculiar. However, the rapidly growing Victorian community had exceptional characteristics.

Before the opening of the museum, displays of exotic, extraordinary, or valuable natural objects were displayed in 'cabinets of curiosities'. These were often random private collections that denoted wealth and intellect and were intended to intrigue the viewer, each object telling its own story. The new public museum, on the other hand, presented comprehensive ranges of preserved plants, animals and various other types of artefacts in a suitably impressive setting.

The audience for these collections came from those who appreciated opportunities for both education and entertainment; the town’s well-read and affluent residents, and the tourists attracted by the emerging elite resort.

The museum was able to cater for this appetite for knowledge as there was an abundant source of local geological and archaeological material. In the early years, these specimens, fossils, and artefacts were primarily sourced from the explorations of Kents Cavern. The Society gained permission from Sir Lawrence Palk to explore the caves and extensive explorations were carried out between 1846 and 1858 by Edward Vivian and William Pengelly. In 1858 Brixham’s Windmill Hill Cavern was discovered, investigations revealing even more ancient animal remains alongside Palaeolithic tools.

As the century progressed, the museum continued to be a focus for both learned residents and renowned visitors, many contributing discoveries and new interpretations across the disciplines of geology, palaeontology, biology, history, and archaeology.

Yet, no institution could remain above wider society.

Provincial museums, such as Torquay’s, took their lead from the British Museum which, back in 1753, had similarly been established with an emphasis on natural history. Yet, by the mid-nineteenth century the capital’s institution had been transformed into a storehouse of treasures gathered from across the world, showcasing Britain’s global dominance and its claimed civilising power.

From the early nineteenth century, explorers, diplomats, and self-taught antiquarians had been acquiring artifacts which were then often donated to local museums. Agatha Christie’s husband Max Mallowan, for example, led digs in Syria and Iraq and his finds ended up in homeland museums.

Having a genuine Egyptian mummy was an especially important status symbol that would attract crowds and give a museum a place on the national stage. Torquay, however, only acquired its mummy in 1956. Donated by Lady Winnaretta Leeds, daughter of sewing machine heir Paris Singer, it was of a young boy who lived in Egypt in about 600 BC. It remains Devon’s only mummy.

Across the nation, public institutions such as museums and schools joined in the task of creating a sense of national unity and pride in British expansion. To this end, all were expected to work to promote Victorian Christian morality, hard work, industry, and progress. A specific objective was the ‘raising up’ of the working-classes, drawing them away from less acceptable forms of entertainment.

The publisher Thomas Greenwood, for example, proclaimed in 1888 that public museums and libraries were as indispensable for municipalities as drainage, the police, and lunatic asylums.

By 1886 Torquay was known as the “the wealthiest town in England” and had a distinct role in the construction of this British identity. The town prided itself as the recreation epicentre of the largest empire in history, a place where the rulers and decision-makers of Empire, its dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and territories, chose for their vacations and retirement.

Following that self-appointed mission, Torquay used its architecture, gardens and parks to promote and embrace the military, scientific and technological advancements of the age.

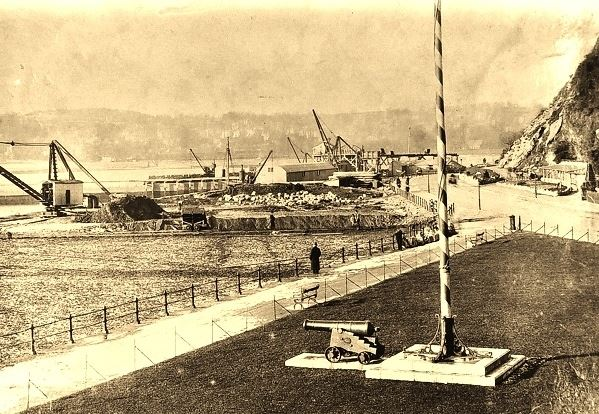

The Royal Navy’s Channel Fleet could often be seen in the Bay while military prowess was celebrated on land. As a reminder of Britain’s victories, near the Strand stood a cannon captured in 1855 in Sebastopol. The Crimean War was one of the first conflicts to use explosive shells, railways, and telegraphs.

For many years a cannon captured during the Crimean War celebrated the nation’s military prowess

For many years a cannon captured during the Crimean War celebrated the nation’s military prowess

The most obvious manifestation of modernity and Britain’s technological advancement was the railway. The opening of the present-day Torre Station in 1848 brought about monumental changes and created a new type of town, the tourist resort. One often-forgotten outcome was the introduction of fixed and reliable time which was then disseminated by the great clock installed for all to see in the Old Town Hall.

Increasing affluence gave Torquay the ability to introduce amenities before other similar-sized towns. Among the first of these was street lighting. For centuries lanterns and candlelight were the sole sources of illumination, but on 8 October 1834 the darkness was banished. Forty gas lamps were installed at the Strand, and two years later the light was extended from Castle Circus to Torre. Both spectators and performers now had more opportunity to engage in ostentatious acts of consumption and display. A local poet wrote:

“Come quick, Jemima, bring your shawl,

Come, come and take my hand,

And let us see the brilliant gas,

Just lighted on the Strand.”

London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 demonstrated to the world that the Empire not only ruled the seas but was also a pioneer in the sciences and a master of the arts. Its centrepiece was the monumental custom-built glass and iron Crystal Palace which was visited by around one-third of the population.

Inspired by the Crystal Palace, Torquay had its own version in the Winter Gardens. Built not far from the Museum in 1878, it was designed as an indoor attraction and to extend the summer season. However, the Gardens struggled to become financially viable, and the massive structure was dismantled and sold to Great Yarmouth in 1904.

Great Yarmouth’s Winter Gardens, bult in Torquay in 1878 before being sold to its Norfolk rival in 1904

Great Yarmouth’s Winter Gardens, bult in Torquay in 1878 before being sold to its Norfolk rival in 1904

Besides grand public buildings, villas and hotels, the Bay’s microclimate allowed the growing of exotic plant species, visual proof of far-reaching power. Wherever the Union flag flew or had influence, the offspring of Empire launched ‘herborising’ expeditions to search for new plants and trees and brought them back to the Bay to study and display.

And so, Torquay’s nineteenth century Museum began as a venue to explore and celebrate the natural world. It then became a vehicle for Victorian ideas of social cohesion and a celebration of the imperial mission.

In much the same way, Torquay’s genesis as a modern town was as a place to appreciate natural beauty. It was similarly transformed into a showcase for the achievements and claims of the British Empire.

Bringing the Empire home Torquay’s microclimate allowed the import of exotic flora

Bringing the Empire home Torquay’s microclimate allowed the import of exotic flora

In Victorian and Edwardian villas and gardens, in parks and imposing public buildings, these aspirations to international and cultural greatness can still be seen in the present day Torquay townscape.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.